A few days ago, I came across notes from a conversation last month while on safari. I’d recapped an exchange with a driver named Antony. He was tasked with getting us to the Livingstone Airport to begin our journey back to Addis. We met Antony after crossing the Zambezi River, and he waited while we cleared yet another immigration checkpoint before officially re-entering Zambia. All border crossings have multiple layers of stress attached in the midst of a global pandemic. That one in particular included the need for an added 7-day “Kaza Visa” purchase, which works interchangeably for both Zimbabwe and Zambia. The ones we’d gotten upon arrival at the Victoria Falls Airport had expired the day prior. What started off sounded like a shakedown at $50 a pop was just the way things worked. But after paying in US Dollars and heading back to the van with Antony, I felt the anxiety rising of what would be the next few days spent getting out of Africa.

As we got underway with precious little margin for error before our flight to Johannesburg, Antony asked where we came from in America in what we’d realize was his compassionate, jovial tone.

“California,” Katie replied. I didn’t correct her by adding more detail. Technically, she spoke for all of us. She lives there. Sarah grew up there. Maya was born in San Francisco. I settled into the slipstream of that summary and figured it would suffice.

“Oh. Is it true then, what they are saying?” Antony asked. I couldn’t help but imagine that more bad news had arisen that morning. We were all so wearied by what was unfolding that I merely stuck out my chin and prepared to take another blow. “Kenny Rogers is dead?”

“Yes,” we all agreed, having heard that news recently. “A tragic loss.” That moment of ironic yet still sad levity allowed us to think of good things. “The Gambler” and Rogers’ duet with Dolly Parton was mentioned. I struggled to name the less popular yet still amazing “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)” that factored so prominently in “The Big Lebowski.” Antony even went masterfully to the deep cut of Kenny’s 1981 “Christmas” album - Rogers first but certainly not last holiday commercial if not melodic masterstroke. We soon settled into a ride that seemed far less stressful. Not much later, we were stopped by a young military officer at a checkpoint who not at all subtly wanted a bribe. Antony talked his way through by threatening to call his boss and we made it to the airport with a small handful of minutes to spare. When saying goodbye, I tipped Antony as if he’d just been our “Baby Driver” - love that movie - for the heist of the century. Yet I fixate on not being able to shake his hand. Will we ever get to shake hands again? I miss doing that more and more every day.

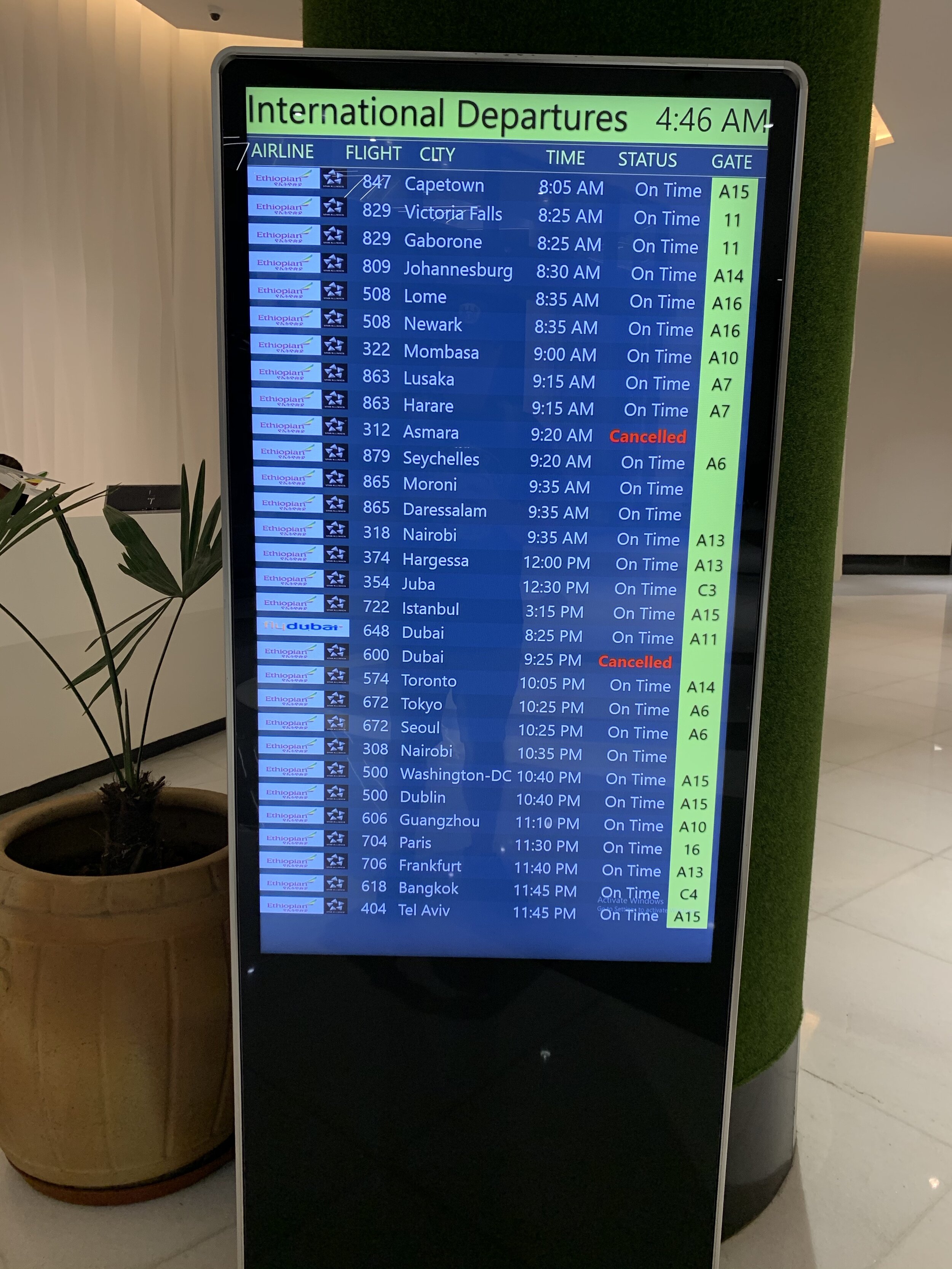

The flight to Joburg was preceded by a warning from the Ethiopian Airlines desk agent. We would be quarantined for 14 days at the Skylight Hotel near the airport in Addis under the brand new orders from Prime MInister Abiy Ahmed. The policy began 10 minutes after midnight. We would arrive at 5 am. There were 50 people on the flight. Citizens or foreigners alike would be subject to the same new system.

Upon arrival, we dove into the new policies being developed on the fly. The chaos included me needing to go behind the desk at the airline’s Transfers desk to type in my credit card information for the ticketing agent. So much for keeping everyone safe, if that would be the aim of the new system. We didn’t pay $125 per night for the family. We paid $125 per person. If we’d been forced to stay for the full 14 days, that would have been over $5200. Just get through Customs, was all we were thinking. We had by now been traveling for a full 24 hours. Maya’s resiliency amazed me.

We got to the hotel. The check-in was a nightmare, but there were only a handful of people ahead of us. There were two large groups of recent arrivals milling about - a pack of Israeli hippies (who looked like they were back from a massive backpacking trek) and young Mormons missionaries. We got two adjoining rooms, one of which wouldn’t be cleaned and fully ready for hours. I spent too much time at the front desk and got to know everyone working there. The chaotic system being employed involved scribbling down on random sheets of paper the room numbers that became available, followed by a shuffling of the various semi-official documents that we had all been given when we arrived at the airport. We ate breakfast. It was a quarantine buffet for everyone from everywhere. The hotel workers did the best they could. They would be crushed by the traumas of bureaucracy to come.

After breakfast, I noticed one of the Israelis who had been checking in at the same time as me arrive back at the hotel in a taxi. I managed to track him down after a frantic search just before we got on an elevator. “Did you get permission to leave the hotel?” I asked.

“Yes. That guy said it was fine,” he replied and pointed to one of the front desk people who I’d spoken with repeatedly.

The unburied lead of this stage of our trip home was that we needed to get our things from our apartment. Everything we brought with us to Ethiopia was there. Everything. We contacted our driver, Teddy, and he agreed to pick us up for the semi-clandestine trip. Meanwhile, Sarah had been communicating with a contact in the Ministry of Health to get official permission to leave our semi-official “transit” quarantine. The policy was so new that no one knew how or what to enforce. That permission arrived at almost the exact minute as Teddy arrived.

The drive to our apartment was harrowing. Teddy couldn’t believe that we were being housed in the way that we described. We couldn’t believe our good luck of being able to leave without restriction. We probably didn’t even describe our safari trip or ask how Teddy’s family was faring. He and wife have three young kids.

The bottom line would be that we had enough time to pack up our things. Which is like saying the invasion of Europe during World War II came together with some planning. We packed up ten bags to check, all weighed and recalibrated to within a frog’s hair of the 23-kilogram or 50-pound limit. We each would also bring a full carry-on and our backpacks. We packed everything in under three hours. While doing so, the wonderful staff at our building heard about what we had to do and how we needed to return home to America. We left some things behind, but we’d later get an Embassy friend who stayed behind in Addis to return with our building’s staff to go through and distribute everything else to people who could use it all. Earlier in the year we’d spoken with Maya about having a “bug out” bag if we needed to leave in an emergency. That, however, was only a dry run for this full effort. It was an amazing test.

While packing things up, we busted a zipper on one of our bags. We had to call a RIDE to help transport the overflow of what we could get into Teddy’s car. The other driver was the worst I ever had in Addis. That harrowing RIDE back to the Skylight ended with a semi-shakedown. But when I looked at the 600+ kg of stuff we’d hauled back, I agreed and let the karma of “he will be judged someday for that” in my mind. As the mensch he’s always been, Teddy said he could find a nearby place to buy a replacement suitcase. He was back in far less than an hour. By the time he dropped it off, the tone of security at the hotel had changed entirely. They wouldn’t even let us say a proper goodbye. We were all crying when we said our thank yous and were shuffled back into our hotel. By the next morning, they wouldn’t even let Sarah’s colleagues who tried to visit and deliver some gifts inside to do so.

We ate a worry-filled dinner as the anxiety washed over us. We’d gotten everything and couldn’t believe our good fortune in doing so. We nervously waited to fly on Emirates Airlines (partnered with Alaska Airlines) through Dubai to Seattle the next afternoon. Sarah and I said “good night” to Maya in her adjoining room. And then we got a message from Alaska Airlines.

Our flight was canceled.

We booked the only seats on a flight leaving Addis the following day. Three business class seats on Ethiopian Airlines to Chicago’s O’Hare leaving late the next night. They would cost us as much as we planned to pay for all the hotels and travel to do a dream 5-week return trip through Europe after the school year ended. We had no choice. Ethiopia was shutting down and we needed to get home to the States.

The next day in the hotel was an anxiety-filled marathon of regret. I spoke with my many new friends at the front desk about needing to stay in our room until the evening. The new policy of all arrivals going into quarantine at this and eventually other hotels meant a steady flow of new people were showing up in waves, stumbling out of shuttles with stunned looks on their faces.

We spent an anxious day thinking about our surroundings. Finally in the evening, we headed to the airport with an amazing porter from the hotel and an equally awesome bus driver. We somehow got our mountain of luggage to the check-in counter. We had to pay for only one bag, but it still cost us $160. The privileges of business class have limits.

We waited for a cancellation that never came. Final communications were sent and many tears were shed. We kept coming back to a stunned recap about our good fortune to have our things in tow and the sad way that we weren’t getting to say goodbye to countless friends. It felt like an chapter without a transition, certainly far from an ending. Or maybe just not the ending we’d imagined.

Our flight left on time. There were many recognizable faces in the 256 passengers onboard, including a running friend from the Saturday morning group who met at the main gate at ICS. He was being shuttled back to Minnesota by his organic foods company under a similar “get home at all costs” order. We tried to enjoy the perks. We shuttled through Dublin and landed at O’Hare.

All Americans should be very bothered by the lax pandemic screening we encountered. No one took our temperatures or even asked us a single question. Uganda, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana, South Africa, and Ethiopia all had systems in place in the past month that we passed through that gave me more confidence than what we do here. Maybe it’s improved. But it was scary and a joke.

However, Chicago was the most Chicago that it has ever been. Which was a brilliant thing. The wit and big-hearted character of the people there make me proud to be an American. We couldn’t check our bags because of a long layover so we spent the day in the Hilton right in the terminal. We ate overpriced snacks and drank $4 drip coffees. That night we flew to Los Angeles with less than 20 people onboard and a crew who hid in the back galley gossiping about how much had changed seemingly overnight. We rented a minivan with most of the seats removed so we could transport our bags to the house we’d spend the next month in. I never unpacked. This weekend, we fly back to Seattle.

Every day we consume way too much news and try to figure out what happened. We are thankful for every moment we spent in Africa and the other countries we were able to visit starting last August. Our plans for the days and months ahead change constantly. We are blessed by good fortune and hopeful about a very uncertain future.

To reflect a bit more on what we saw in March - all of Africa and the larger world had new quarantine or lockdown policies being tested. Ethiopia’s put in place an amalgam of approaches. As had been the case in all the countries we visited, you had your temperature taken at every turn. Border crossings between Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Botswana required it. The airport in Addis was very much under these orders. Actual COVID-19 testing was newly possible after Alibaba founder Jack Ma delivered one million test kits to the continent. Ethiopian Airlines had taken on the task of distributing them to the 54 nations of Africa. As of this writing, 52 of those nations have tested positive for the coronavirus (only the Kingdom of Lesotho and the disputed territory of Western Sahara do not current report COVID-19 cases).

The current state of COVID-19 in Ethiopia is very much an open question. They have only confirmed 131 cases. Here in America, we have over one million. Comparisons are very hard, even for the professionals. We have some powerful anecdotal insights that I would like to elaborate upon, but I don’t really want to veer into armchair epidemiology which works against the mission of those trying to lead us through this pandemic.

Ethiopia declared a “State of Emergency” and indefinitely postponed the national elections previously scheduled for August. Almost daily, we read about what’s happening there. I still monitor all the communications coming from Maya’s school and the community around it. Sarah is in daily communication with her colleagues at St. Paul Hospital. Zoom gets used every day. Like so many people during this pandemic, we’re feeling our way through the dark - day by day. There will be many more images for us to share in the not-too-distant future. For now, however, these few pictures from our last days in Africa are followed by another few from our first days in California. We will head home to Seattle on Saturday. Soon, I will post more and clean up everything above. As will become apparent, my haste in doing so has its reasons. A final reflection on Addis, nonetheless, follows this small gallery.